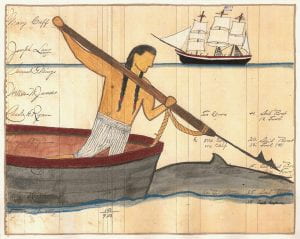

The Harpooneeris a project that I have wanted to take on for many years. He is the embodiment of Wampanoag whalemen from the earliest years of colonial, commercial whaling until its end. He isAbsalom Boston, Thomas Boston, George Cook, Marcelus Cook, Paul Cuffe, William Wallace James, Amos Haskins, Samuel Mingo, Thomas Mumford, Amos Smalley, and countless others. After all, “Ship-owners come to their cottages, making them offers and persuading them to accept them…Rarely is Gay Head visited for any other purpose,” said Edward Crandall, who visited the Vineyard in 1807” (Flemming). I chose to draw a Wampanoag whaler for this particular project in conversation with both Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, and Nancy Shoemaker’s Living with Whales, to put a face to the names of all the Wampanoag men whose portraits were never painted and whose daguerreotypes were never taken. Ironically, the Harpooneer does not have a face. This is for two particular reasons: in many Native societies, including my own, we do not put faces on dolls or drawings of humans. This harkens back to a cultural teaching of humility and a warning against vanity, and therefore prevails in many of our artforms. This man also does not have a face because he is not representative of any one Wampanoag man. His broad shoulders and tall stature are characteristic of descriptions of Wampanoag men (contrasted with colonial descriptions of Narragansett men, who are tall and lean). I gave him my husband’s hairline, an identifier of Wampanoag men. He is a representation of generations of men involved in the industry.

My vision of the finish product, changed some from how it was executed. I knew that I would be working on a facsimile of an original whale logbook, crew list, chantey music sheet or ledger from a Native community. Of course, it would be incredible to work on original, however, these materials are so precious to our communities, we must preserve them in perpetuity. I knew that I wanted a ship on the horizon, and a whaleboat filled with a crew of men setting out to harpoon a whale, with a Native harpooneer aboard, but as I continued to sketch out my plans, the Harpooneer came to the tip of my pencil, with my focus being solely upon him. Unintentionally, he began to fill my page. Each line sketched was a conversation with him, as memories of oral histories and documented knowledge about the above whalers came to mind. The family stories that will be passed down to my son and the deep history that goes with it are imbedded in this Harpooneer.

Ledger art is a common fine art form among many Plains tribal artists, with many contemporary artists showcasing and selling their work at Santa Fe Indian Market (SWAIA), or exhibiting in fine art institutions such as the Peabody Essex Museum. While Wampanoag men were whaling at sea during the mid-nineteenth century, the Plains people, such as the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ(the Lakȟóta and Dakȟóta) people, among others were fighting against the United States during the “Indian Wars.” Traditionally, men would paint pictographic narratives on buffalo robes, elk hides and tipis as a way to record their successes in battle and bring honor to their communities (Pearce).

As time continued on, paper became the medium on which the artists would work: “By the 1840s, paper was more readily available [than hides] in the form of autograph books, sketch pads, note paper, stationary, and balance sheets—which were generically called ledger books when Plains Indians used them for their picture stories. Some of the balance sheets had been used to record white profits based on Indian losses” (Pearce 2). Women’s participation in ledger art had a slow start, beginning in the 1920s with a Kiowa Agency woman named Susie Peters, who received ostracization from her community for participating in an “unladylike activity,” such as painting (in Očhéthi Šakówiŋ societies, certain mediums were/are gender dependent).

Ledger art practiced by women did not gain wide acceptance until the latter half of the twentieth century with artists such as Sharron Atone Harjo (Kiowa), Linda Haukass (Sincangu Lakota), Dolores Purdy Corcoran (Caddo) and Colleen Cutschall (Oglala Lakota), (Pearce). The daughters and relatives of these women are continuing this artform, and are my artist contemporaries, and help to inform my work. I’d like to acknowledge Tahnee Atoneharjo-Growingthunder (Kiowa/Creek/Seminole), Lauren Good Day Giagio (Hidatsa/Arikara/Blackfeet/Plains Cree), and Wakeah Jhane (Comanche/Blackfeet/Kiowa).

Running parallel to this artform is the artwork kept by ship captains and crewmembers as they entered into their logbooks the daily activities. While perusing the online collection of the Nicholson Logbook Collection at the Providence Public Library, I encountered many logbooks with sketches of ships and whales, with some illustrated by Wampanoag men. Though not “ledger art,” with respect to coloration, and design of Plains people, this alternative form of ledger art is still inherently Indigenous art when in a logbook kept by a Wampanoag whaler, “Their art was important in ‘confirming and maintaining kinship relations,’ bringing prestige to their families, and preserving the basic values of their tribe. The source of this complementarity was ‘deeply embedded in [their] tribal memories’” (Pearce 1).

I spent one afternoon looking through a Wampanoag logbook, but the fragility and transparency of the pages would prove difficult to get a quality facsimile for what I wanted to create. I came upon three valuation lists for the town of “Gay Head” [Aquinnah], Martha’s Vineyard: 1890, 1893, and 1895. I carefully looked through them to find a page that would suit my needs. I chose a page out of the 1893 Valuation List as it holds the names of my husband’s antecedents, Mary Cuff, William Wallace James and Benjamin Attaquin, as well as names recognizable to anyone with a basic history of Wampanoag whalers: Samuel Mingo and Amos Haskins. Because of the size of the valuation lists (20”x20”), I was limited in what I could properly scan and print, and only chose a section of one of the pages that holds the name. The valuation lists out the assets held by each citizen. Though, not on the final artwork itself, the valuation of assets and land holdings of the whaling men were significantly higher than that of anyone else (by thousands of dollars in some cases).

In the tradition of contemporary ledger art, I chose to work with Prismacolor colored pencils, watercolors, India ink, pen, and acrylic marker. After carefully sketching in pencil, I outlined the forms of the ship, the Harpooneer, his harpoon and his whaleboat in black ink. I then worked on the harpoon, Harpooneer’s skin tone, hair, sailor slops and the whale, whaleboat, ship and water in that order. I finished it with a light border of copper acrylic paint. While working, I chose to listen to J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, which is complete with a musical score and dramatizations. It helped me to focus upon the task without overthinking my linework—which is often a problem for me. I second guess myself and my abilities in drawing—which is why I am mostly a beadwork and porcupine quillwork artist. However, after this piece, I am interested in creating more ledger art, speaking to the various aspects of whaling: from the bidding farewell to the whaleships out of New Bedford to the cutting-in of the whale to the try-works, to the return home. I hope to create a series of pieces reflecting Indigenous involvement in the nineteenth century whaling industry.

The ship featured in the background, is a nod to the Charles W. Morgan, which I had the pleasure of visiting in 2015 in New Bedford, Massachusetts. The Morgan carried many Wampanoag workers from my husband’s family over the years. The Morgan is painted black with a white stripe and a maroon hull, but I also reversed the color order as a reference to the “Observations in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, which stated that every day, you would see 20-30 of the Gay Head Indian ships sailing by, and that you knew that it was the Indian ships, because their masts and top decks were painted red” (Perry 2019).

While drawing, I spoke with my husband, Jonathan Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag), and asked him about some of the names on the valuation list I chose. A name that I had heard of before, William Wallace James is almost centrally located in the left-hand column. William Wallace James served on multiple vessels, most notably the Charles W. Morgan. He lost his brother, wife, and child in the same year while he was at sea. It’s believed that after this, he jumped ship, but it is possible that he left his ship after completing his whaling duties. He left the whaling world while his ship was in port in New Zealand. He remarried a Māori woman and his descendants are still there today (Perry).

In working on this art project, I feel as if my time in ENG 396: Literature of the Seahas come full circle. I’ve completed not only this course, but I feel as if I have successfully married my personal research and interest with my artistic skills, and family history. I completed reading Moby Dick, which some will consider a daunting task, and through it, I could imagine every character except Tashtego, “an unmixed Indian from Gay Head, the most westerly promontory of Martha’s Vineyard, where there still exists the last remnant of a village of red men, which has long supplied the neighboring island of Nantucket with many of her most daring harpooneers.” (Melville 100). I think after completing The Harpooneer, I understand why I cannot picture Tashtego. He is the same as The Harpooneer: he is the quintessence of all Wampanoag whalers. He cannot have a face, because he isthe community. He is a Cuff, a James, a Haskins, a Mingo a Mye. He is every Wampanoag man that ever set foot on a ship. He is every cabin boy, every harpooner, every first mate, every captain. He is the man that provided for our communities, he is the man who lit the world.

Works Cited

Flemming, Gregory. “Dangerous Waters.” Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, 1 Feb. 2016, www.mvmagazine.com/news/2014/05/01/dangerous-waters.

Good Day, Lauren. “Lauren Good Day.” Lauren Good Day, laurengoodday.com/.

Hopkins, Leah. “Oral History with Jonathan Perry.” 6 May 2019.

James-Perry, Elizabeth. “Thomas S. Boston, A 19th Century Wampanoag Musician.” Dawnland Voices, Dawnland Voices, 3 Oct. 2016, dawnlandvoices.org/elizabeth-james-perry-issue-2/.

Jhane, Wakeah. “Wakeah Jhane.” Wakeah Jhane, www.wakeahjhane.com/.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick: an Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism. Edited by Hershel Parker, W. W. Norton Et Company, 2018.

Pearce, Richard. Women and Ledger Art: Four Contemporary Native American Artists. University of Arizona Press, 2013.

Shoemaker, Nancy. Living with Whales: Documents and Oral Histories of Native New England Whaling History. Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2014.

This is wonderful, Leah! I love your artwork and the very last line of your essay is terrific! What a great close!