**Note: edited version uploaded April 1**

The “Savage” and the “Leviathan:” The Commodification of the Bodies of Indigenous Men and Whales in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

The term “savage” appears 49 times in Herman Melville’s, 1851 novel, Moby-Dick, and “Leviathan” appears 71 times. These two expressions, at face value, conjure fear, thoughts of the unknown—beastly characters as a manifestation of the untamed natural state of the world, an absence of civilization and most horrifically the potential of cannibalism. Melville uses both savage and leviathan to describe what today we might call otherness, or the Other. During the nineteenth century, the terms could be used synonymously to describe an entity considered sub-human, at the time when non-Western cultures had not achieved the status of “civilization,” (Tylor 48) and were thus considered closer nature, akin to beasts. Writing for an 1851 audience in pre-Civil War, Industrial America, Melville provides an in depth social and cultural commentary and critique on the many facets of mid-nineteenth century capitalism. Without directly stating that excessive consumption and capital greed is the novel’s Leviathan that readers should be concerned about, the texts leads them to this conclusion through the characters on the Pequodand their journey to hunt the great White Whale. In other words, Melville crafted a text that carefully walks his audience through their own fragilities in hopes of conveying messages of caution and understanding of, and ultimately reflection on the fallacies of capitalism. Melville creates a looking glass through which his audience can view the whaling industry as the commodification of Brown, Black and Grey bodies, and he challenges this commodification by imparting humanity and sentience upon both the Pequod’s harpooneers, and the whales themselves.

The whaling industry, built along the Southern New England Coastline, was the amalgamation of Indigenous and Colonial practices of hunting whales, first for subsistence and material use, and then eventually becoming an ecologically devastating industry onto which New England Indigenous men had but little choice to participate in. Melville writes of Tashtego, in Chapter 27, Knights and Squires, “But no longer snuffing in the trail of the wild beasts of the woodland, Tashtego now hunted in the wake of the great whales of the sea; the unerring harpoon of the son fitly replacing the infallible arrow of the sires” (Melville 100). Traditionally, Indigenous people would hunt whales for food, but due to the effects of colonization of the New England coastline, Native men were forced to support their families through industrial whaling, or where forced to sign aboard as slaves or indentured servants to pay off their family’s debt, “the capitalist foundations of the early whaling industry, which pitted a white merchant class against Indian laborers forced to hunt whales to pay off debts…on Long Island, debt leading to indenture had a major role in regulating Indian labor.” (Shoemaker 39). Patterns such as this continued globally, affecting indigenous populations in every ocean.

Whaling became a multicultural, multiethnic and multinational venture, but still was controlled by Euro-American colonial powers. Ishmael describes the streets of New Bedford, Massachusetts, the Whaling City, “In these last-mentioned haunts you see only sailors; but in New Bedford, actual cannibals stand chatting at street corners; savages outright; many of whom yet carry on their bones unholy flesh” (Melville 38). The term “savages,” refers outright to people of color—indigenous people—to America, the South Seas, Africa and other areas abroad. With this othering, there was a commodification of indigenous whalemen—coastal New England Native nations, such as the Wampanoag, Shinnecock, Narragansett, Pequot and Montauk—represented in Moby-Dickby Tashtego, an Aquinnah Wampanoag from Gay Head, Martha’s Vineyard; men from coastal Africa, represented by Daggoo, and the South Pacific and Hawaiian islanders represented by Queequeg. Melville uses these three characters as cultural ambassadors for each part of the world that they represent. Though this may appear as forward thinking for the nineteenth century, this inadvertently forces the audience to recognize these three men, and by extension, their distinct communities to serve as the representations for entire continents and archipelagoes of ethnically and culturally diverse people. The Pequod, and by extension, whaling industry would be defunct and non-existent without the labor and contributions of these Brown and Black men.

The Pequod’s harpooneers, Queequeg, Tashtego and Daggoo are pawns in Ahab’s own megalomaniac game of hunting the White Whale, but are also symbolic of the capitalistic exploitation of communities of color, which is caused by the othering by the aggressors. The way in which Tashtego, Daggoo and Queequeg are described are as savages, pagans, and cannibals, causes the audience to reaffirm their preconceived notions of indigenous populations as something to fear. The harpooneers show compassion for Ishmael, but in turn, Melville is leading the reader to show compassion for the harpooneers. Melville takes the reader past their initial fears and assumptions by first introducing them in the familiar contemporary context, but then throughout the course of the novel, he begins to break down barriers and erodes the prejudicial through process by imparting familiar humanistic characteristics. Melville sets up the character of Queequeg in Chapter 2: The Spouter Innby first describing the fear of his Browness, then of his savagery: “I could not help it, but I began to feel suspicious of this ‘dark complexioned’ harpooneer” (26), “But then what to make of his unearthly complexion, part of it, I mean, lying round about, and completely independent of the squares of tattooing” (31). Interestingly, Ishmael goes on to say, “Ignorance is the parent of fear” (31), alluding to the unfamiliarity with Queequeg’s culture an background is the source of his fear—which the reader learns that Queequeg becomes Ishmael’s closest companion, despite their cultural differences. Ishmael continues throughout Chapter 2 to describe Queequeg’s savage and unfamiliar manner, “It was now quite plain that he must be some abominable savage or other shipped aboard of a whaleman in the South Seas…” (32). Ishmael uses words such as “savage,” “heathen,” (32), and “cannibal” to continue to describe Queequeg (33), only to in the next chapter, The Counterpane, to state, “Queequeg, under the circumstances, this is a very civilized overture; but, the truth is, these savages have an innate sense of delicacy, say what you will; it is marvelous how essentially polite they are…he treated me with so much civility and consideration, while I was guilty of great rudeness” (35). Throughout these introductory chapters, the audience comes to see and know some background of Queequeg through Ishmael’s eyes. Melville continues to use the term savage, but contrasts the terminology with descriptions of Queequeg’s civility, causing the audience to form compassion and a love for Queequeg, where they would not in reality be able to accept him past his looks.

The two other “savages,” that the reader encounters are Tashtego, “an unmixed Indian from Gay Head, the most westerly promontory of Martha’s Vineyard, where there still exists the last remnant of a village of red men, which has long suppled the neighboring island of Nantucket with many of her most daring harpooneers…(100). Ishmael continues on to describe his physical characteristics, but sums up the description by stating, “you would almost have credited the superstitions of some of the earlier Puritans, and half believed this wild Indian to be a son of the Prince of the Powers of the Air” (100), alluding to Satan. This satanic imagery leads the audience down another fear-inducing path with reference to the Other. Daggoo, who “retained all his barbaric virtues,” “voluntarily shipped aboard a whaler,” off of the Western Coast of Africa (101). Although less is written about Daggoo than Queequeg and Tashtego, he still serves as the ambassador to all of Africa and its people—separate from what Melville’s audience knows as Black America. “But for all this, the great negro was wonderfully abstemious, not to say dainty” (123).

The “savagery” of the harpooneers is sharply contrasted by the presumed civility of the three officers, Starbuck, Stubb and Flask, and Captain Ahab—but the humanity of these officers is not as apparent when compared to the harpooneers. Chapter 34,The Cabin-Table, describes the relationship, or lack thereof between the officers at the dinner table as filled with protocol and order. First, Captain Ahab must come to the table, then Starbuck, then Stubb, then Flask. No conversation nor interaction occurs, and the men sit in silence. The following meal of the harpooneers is filled with laughter and comradery:

In strange contrast to the hardly tolerable constraint and nameless invisible domineerings of the captain’s table, was the entire care-free license and ease, the almost frantic democracy of those inferior fellows the harpooneers. While their masters, the mates, seemed afraid of the sound of the hinges of their own jaws, the harpooneers chewed their food with such a relish that there was a report to it. They dined like lords…(123)

The three officers and the captain represent the order on the ship and function as familiars that the audience can identify with, hailing from Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket. These three officers are myrmidons, who despite the megalomania of Ahab, never seize the opportunity to confront and stop him from his harsh obsessive hunt for the White Whale. The complacency of the officers with Ahab’s obsession, although they morally are unsure of it themselves are equally responsible for the doom of the Pequodand the death of the crew. Melville uses these officers as stand-ins for consumers within a capitalistic society. Consumers are bound by the hegemonic practices, and are unable to escape their role within the Leviathan. Consumers in the mid-Nineteenth Century were families that used whale oil to light their lamps, ladies who wore whalebone corsets, seamstresses who needed spermaceti oil to lubricate their machines, soap makers among others. The proprietors and captains benefited greatly off this demand, and provided the supply at the expense of massive populations of whales.

Melville, similarly to the harpooneers, introduces the whale as something to be feared—a Leviathan, a monster, “The picture represents a Cape-Horner in a great hurricane; the half-foundered ship weltering there with its three dismantled masts alone visible; and an exasperated whale, purposing to spring clean over the craft, is in the enormous act of impaling himself upon the three mast-heads” (24). This quote foreshadows the demise of the Pequod and its crew, but also introduces fear and mystery of the fearsome whales. But Melville spends significant time describing the classification and the biology of whales, helping the reader, who has likely never seen, or will ever see a whale to imagine them as grand, graceful creatures. It is when Ishmael describes living and dying whales however, that the reader is led to develop a sense of compassion and pity for the great beings:

“And now abating in his flurry, the whale once more rolled out into view; surging from side to side; spasmodically dilating and contracting his spout-hole, with sharp, cracking, agonized respirations. At last, gush after gush of clotted red gore, as if it had been the purple lees of red wine, shot into the frighted air; and falling back again, ran dripping down his motionless flanks into the sea. His heart had burst!” (222)

This is the first moment in the novel where a whale is successfully hunted and killed. The excitement of the pursuit of the whale is marred by shock value of this passage in the graphic details, and more specifically in the death throes and final breaths of the whale—much like the descriptions of soldiers on the front lines of battle. This passage causes the reader to pause and reflect on the sentiency of the whale. Melville in Chapter 87, The Grand Armada, takes the audience a step further, and imparts human characteristics in order to glean emotion and empathy from his readers. In the following eloquent and otherworldly passage, Ishmael describes the crew’s interaction with a pod of whales:

But far beneath this wondrous world upon the surface, another and still stranger world met our eyes as we gazed over the side. For, suspended in those watery vaults, floated the forms of the nursing mothers of the whales, and those that by their enormous girth seemed shortly to become mothers. The lake, as I have hinted, was to a considerable depth exceedingly transparent; and as human infants while suckling will calmly and fixedly gaze away from the breast, as if leading two different lives at the time; and while yet drawing mortal nourishment, be still spiritually feasting upon some unearthly reminiscence; – even so did the young of these whales seem looking up towards us, but not at us, as if we were but a bit of Gulf-weed in their new-born sight. Floating on their sides, the mothers also seemed quietly eyeing us. One of these little infants, that from certain queer tokens seemed hardly a day old, might have measured some fourteen feet in length, and some six feet in girth. He was a little frisky; though as yet his body seemed scarce yet recovered from that irksome position it had so lately occupied in the maternal reticule; where, tail to head, and all ready for the final spring, the unborn whale lies bent like a Tartar’s bow. The delicate side- fins, and the palms of his flukes, still freshly retained the plaited crumpled appearance of a baby’s ears newly arrived from foreign parts. (289)

This incredible passage parallels whale calves with human infants, and like Queequeg, Tashtego and Daggoo, provides and opportunity for compassion, as these sucking whales and their nursing mothers become the voice and ambassadors to conservation of these majestic and mysterious beings. The ethereal world that the whales and their hunters float in seems suspended in time. This effect allows the reader to step away from their perception of the noble whaleman as the hero battling against the great Leviathan, and refocus the lens to empathize with these magnificent creatures through relatable moments that we share as mammals—such when a mother bonds with her own newborn. The intimacy described in this scene between the men and the whales shatters the wall between the Self and the Other, between the hunter and the hunted and allows for a moment of equilibrium on either side of the water’s surface. The beauty that is displayed in this one moment is taken away and slaughtered for commodification the next. Likewise in Chapter 81, The Virgin, Melville anthropomorphizes a dying whale, pursued by the Pequod’s crew, and likens it to an old man who has encountered a long and hard life: “For all his old age, and his one arm, and his blind eyes, he must die the death and be murdered, in order to light the gay bridals and other merry-makings of men, and also to illuminate the solemn churches that preach unconditional inoffensiveness by all to all” (270). Melville chooses to use the term, murder. This is the conscious, premeditated choice to take this whale’s life prematurely, although it was in the winter of its long life. Instead of choosing to use words such as “ending its misery,” or the like, murderevokes feelings of sin and disgrace—far from the characteristic of a noble whaleman.

Just as the bodies of these indigenous harpooneers are necessary in the industry, so are the grey bodies of the whales. The commodification of these two character groupings are stand-ins for the thousands of men of color and thousands of whales that were exploited during the whaling industry for capital gain of Euro-American colonial powers. The true monster, the true leviathan is not the Other, the Savage, the Whale, but is represented by the cannibalistic whaling industry that ate itself, embodied by Ahab, and his megalomania and his revenge on the White Whale, “for there is no folly of the beasts of the earth which is not infinitely outdone by the madness of men” (287).

Works Cited

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick: an Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism. Edited by Hershel Parker, W. W. Norton Et Company, 2018.

Shoemaker, Nancy. Living with Whales: Documents and Oral Histories of Native New England Whaling History. University of Massachusetts Press, 2014.

Morgan, Lewis Henry. Ancient Society: Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization. Kessinger, 2008.

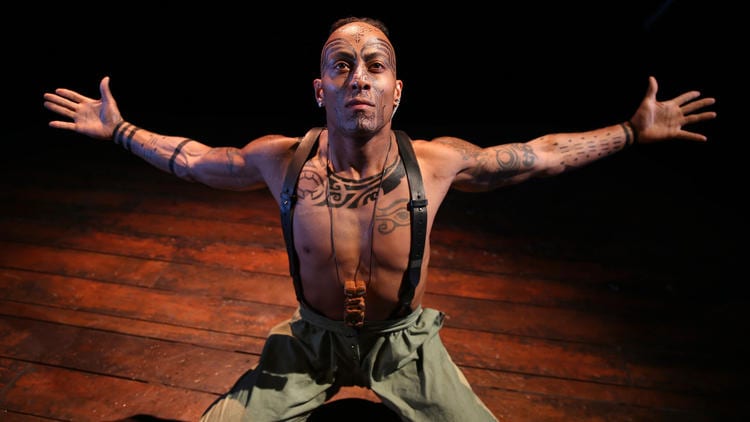

Leah, what is the citation information for your featured image?

Molzahn, Laura. “Dancing Queequeg, the Secret Weapon in ‘Moby Dick’.” Chicagotribune.com, Chicago Tribune, 30 July 2015, http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/theater/dance/ct-moby-dick-fleming-choreography-20150730-column.html.