The Odyssey and Its Impact on the Rhetoric of Womanhood

In a famous 2017 Saturday Night Live “Weekend Update” skit, comedian Tina Fey binges on a sheet cake to express rage over the Unite the Right rally that took place on the grounds of the University of Virginia on August 11, 2017. In the skit, Fey notes that she remained a virgin for the entirety of her college career then exhorts “all good, sane Americans to treat [upcoming] rallies like the opening of a thoughtful movie with two female leads: don’t show up.” She closes with a non-sequitur: “And, as Thomas Jefferson once said, ‘Who’s that hot, light-skinned girl over by the butter churn?’” Rereading Homer’s The Odyssey in tandem with The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Written by Himself and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad: The Myth of Penelope and Odysseus, certain tropes about womanhood appear again and again: A woman’s worth is not inherent. It is conferred. A woman’s virtue is noteworthy. Her intellect is not. And a woman’s beauty—that’s a questionable asset.

In the diegesis of The Odyssey, women’s relative worthiness is assessed in one of two ways: via virginity or faithfulness. Nearly all female figures in the epic are held to this standard. Athena, the only female character with true agency, is a virgin. Fellow immortals Calypso and Circe do not have Athena’s power; they must yield Odysseus at the command of Zeus. Penelope is alternately described as blameless, wise, and prudent. Seventeen years after her husband’s disappearance, she still weeps with the despair of a newly widowed woman. And yet, when complimented by Eurymachus in Book 18, Penelope denies her worth:

No, the deathless gods destroyed my looks that day/

The Greeks embarked for Troy, and my own husband/

Odysseus went with them. If he came/

And started taking care of me again,/

I would regain my good name and my beauty. (Homer 417)

Odysseus’ leaving is Penelope’s shame. In her husband’s absence and despite her blameless conduct, Penelope is compromised. Odysseus must return to Ithaca in order for Penelope’s “good name” to be restored to her. In using the expression “good name,” the narrator is explicitly noting that a woman’s fidelity is not enough. To maintain her virtue, a woman must, in effect, deny any compliment, any thought even, that she is worthwhile in her husband’s absence.

This rhetoric of a woman’s honor being entwined with shame is echoed by Equiano in his account of life before his abduction and enslavement. In his native community, adultery is a woman’s crime for which she would be either sold into slavery or put to death “so sacred among [the men] is the honour of the marriage bed, and so jealous are they of the fidelity of their wives” (Equiano 21). In speaking of marriage customs, Equiano describes a culture quite close to that of the Greeks’ with regard to women. A woman is first owned by her parents and ownership is conferred to the husband at marriage. Equiano writes “the parents of the bridegroom present gifts to those of the bride, whose property she is looked upon before marriage; but after it she is esteemed to be the sole property of her husband” (ibid). In the world of Equiano’s childhood, women are accrued. It is acceptable for men to have a second or even multiple paramours, he writes. And no wonder. The freed women of Equiano’s childhood were, he says, ”uncommonly graceful, alert, and modest to a degree of bashfulness, nor do I remember to have ever heard of an instance of incontinence among them before marriage. They are also remarkably cheerful” (25). The note on their cheerfulness is surprising as later, when at his first church service, Equiano, upon seeing the white women there, notes “I thought they were not so modest and shamefaced as the African women” (48). Again, there is that idea that an esteemed woman is a shamefaced woman. Are Equiano’s men in their sanctioned unfaithfulness and women in their modesty “to a degree of bashfulness” not the heirs to the fictional characters of Odysseus and Penelope?

Intellect as an attribute is not as prized as shame, fidelity, or beauty in the world of The Odyssey. Penelope’s gifts in this area are evaluated by how well they are applied to advancing her husband’s aims. Though a queen, Penelope lives in a constant state of precarity. In marrying, she does her husband the greatest dishonor but in refusing she risks her son’s inheritance. Her only hope is Odysseus’ return. Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad posits that marriage to one of the suitors will be further debasement still for Penelope. Her suitors are malignant creatures who insult her and mean her harm:

What’s to stop one of us from just grabbing the old cow and making off with her? No, lads, that would be cheating. You know our bargain—whoever gets the prize gives out respectable gifts to the others, we’re agreed, right? We’re all in this together, do or die. You do, she dies, because whoever wins has to fuck her to death, hahaha. (106)

In the worlds of The Odyssey and certainly The Penelopiad, the rhetoric is savage and thuggery begets fraternity. Sex is another form of violence, and rape of one’s wife, a laughing matter. Noblewomen, like Penelope, are a means for a man to elevate himself, but that doesn’t mean they are held in high regard. Atwood’s suitors’ use of words and phrases like “old bitch” and “cow” and Homer’s narrator’s use of “dog” make clear that a woman’s status is not equivalent to a man’s in these worlds. She is chattel—a concept Christina Sharpe highlights in In the Wake: On Blackness and Being when quoting June Jordan who writes of the condition of female slaves in “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America or Something like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley”:

“Come to a country to be docile and dumb, to be big and breeding, easily, to be turkey/horse/cow . . . to be bed bait: to be legally spread legs for rape by the master/the master’s son/the master’s overseer/the master’s visiting nephew: to be nothing human.” (Sharpe 41)

And if a woman is chattel, her beauty, even when prized, can be a serious liability.

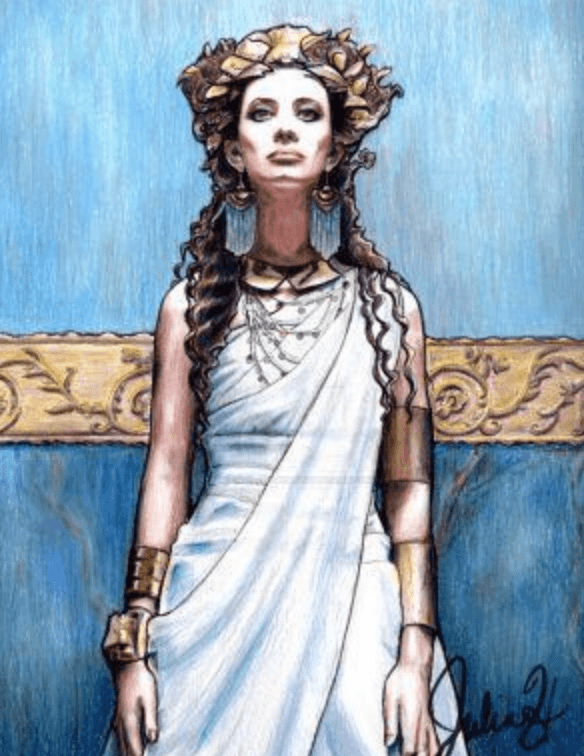

In The Odyssey, the only character to escape punishment for her transgressions is the beautiful, desirable Helen arguably because she is more trophy than wife to her husband. What is most interesting about Helen’s and Menelaus’ story is the gap in the narrative. The text does not speak of how Helen and Menelaus reconciled after her affair with Paris, though it is clear that they have. When in Book 4 Telemachus visits the pair, Helen has clearly resumed her position as queen as she:

emerges from her high-ceilinged, fragrant bedroom,/ like Artemis, who carries golden arrows./ Adraste set a special chair for her, Alcippe spread upon it soft, wool blankets,/and Phylo brought a silver sewing basket,/given to her by Alcandre, the wife/of Polybus, who lived in Thebes, in Egypt,/where people have extraordinary wealth. (Homer 156)

Arguably, Helen is valued because she is not quite—or not just—a wife. Like the special chair and the soft, wool blankets and the silver sewing basket, Helen is object, property, and prize to Menelaus. His honor is restored when Helen is returned to him because she is a thing stolen, not the woman who made him a cuckold. The text gives no discernable indication of marital tension. Helen calls Menelaus her “fine, handsome, clever husband” and Menelaus addresses her as “wife” (Homer 160). Helen’s defense of her infidelity, an affair that caused such great loss of human life, amounts to less than a sentence in the poem and is the Hellenic version of the devil made me do it: “I wish that Aphrodite had not made me/go crazy, when she took me from my country” (ibid). Of course, in invoking the goddess of love, the text plants doubt that all is right in Helen and Menelaus’ marriage. Is Helen’s statement really avowing her love for Paris still? Couldn’t Helen be saying that she wishes love had not made her act rashly? Is she a victim of her beauty and Aphrodite’s folly? Homer’s narrator is cryptic on this point but clear in the assertion that Helen’s beauty brought bad luck to many, herself included.

Tina Fey’s sheet-cake skit affirms that the ways in which society talks about women haven’t changed much since 750 BC. That Thomas Jefferson’s raping of Sally Hemings invokes laughter, that women’s intellectual work is not worth the price of a movie ticket, that Sigmund Freud used the dichotomy that is virginity and sluttery to characterize men’s impotence within a committed relationship: this is the legacy of The Odyssey. In Homer’s world, it appears that it is Helen, not Penelope, who is peerless. Helen, after all, is the one woman who has sexual agency without repercussions. Only the Catholics’ Virgin Mary enjoys equal status. But Helen and Mary’s vaulted position comes at the cost of their humanity, and their legacies, lascivious beauty and perpetual virginity, have been problematic for women ever since. What choice is Madonna or whore? No choice at all. It’s no wonder Tina Fey is screaming into her cake.

—Marybeth Reilly-McGreen

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. Penelopiad. Grove, 2019.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2001.

Homer. The Odyssey. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2018

Saturday Night Live. YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVvpXZxXWZU&t=2s.

Sharpe, Christina Elizabeth. In the Wake: on Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.

Wheatley, Phillis. Poems of Phillis Wheatley: a Native African and a Slave. Applewood Books, 1969.